A personal diary that keeps track of my listening fodder, with mixed observations on classical music and a sprinkle of jazz and pop.

zondag 30 oktober 2011

Comment: A review of Myer Fredman's 'Maestro'

I just posted a review of Myer Fredman's Maestro, Conductor or Metro-Gnome? Reflections from the Rostrum. I gave it four stars, which is generous for this rather rambling collection of personal reminiscences and tidbits. Unfortunately, what ultimately makes a great conductor Fredman is not able to elucidate. I'll guess we'll never know.

zaterdag 29 oktober 2011

Roussel: Le Festin d'Araignée, Fragments Symphoniques - Debussy: Jeux

Roussel's ballet Le Festin d'Araignée was premiered in april 1913, barely a month before Debussy's Jeux. I have just one recording of the fragments symphoniques (not the full ballet) in my collection: a live 1974 radio recording of the Concertgebouw Orchestra led by Haitink. It's a charming work, with the poise, delicacy and clarity of line so typical for this composer. Le Festin is scored for a very classic ('Mannheim') orchestra (with added harp and some percussion). However, the work predates Bacchus et Ariane by almost 20 years and can still be considered 'early Roussel' (only his post-war Second Symphony would herald his mature style). The influence of Debussy is very obvious throughout but we can also hear a sniff of Ravel (Rhapsodie Espagnole, Ma Mère L'Oye (premiered a year earlier)), a whiff of Wagner (Siegfried Idyll) and a hint of Tchaikovsky (Nutcracker). The music that accompanies the 'Hatching of the Mayfly' (L'Eclosion de l'Ephemère'), a broad and mysterious theme for the strings punctured with questioning motifs in the winds, even reminded me of Dvorak in his most wistful moments (we know for a fact that the Bohemian connection ran in the opposite direction as Roussel, from 1923 onwards up to his death in 1937, taught and coached Bohuslav Martinu). Haitink's performance of Roussel's ballet-pantomime is serviceable, maybe even good, but it's not great. I have the feeling there is more to be drawn from this music.

The 14-CD set with Haitink radio recordings also contains a 1967 reading of Debussy's Jeux and this struck me as very accomplished. In its consummate combination of atmosphere and athleticism it maybe even surpasses his later studio recording. Jeux is a work that continues to startle me with its kaleidoscopic richness. As a listener one can only yield and drift along with the momentary changing moods and dynamics. I will certainly return to this recording.

I followed up with a 1994 Jeux by Jukka-Pekka Saraste and the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra (recently re-issued as part of a bargain-priced 5CD box with Virgin recordings). It's two minutes faster than Haitink and to me it sounds curiously anemic. The indifferent digital sound doesn't help. Jeux has to be perfectly moulded and played. If not, it quickly bores and that is what happened to me when I listened to this recording.

The 14-CD set with Haitink radio recordings also contains a 1967 reading of Debussy's Jeux and this struck me as very accomplished. In its consummate combination of atmosphere and athleticism it maybe even surpasses his later studio recording. Jeux is a work that continues to startle me with its kaleidoscopic richness. As a listener one can only yield and drift along with the momentary changing moods and dynamics. I will certainly return to this recording.

I followed up with a 1994 Jeux by Jukka-Pekka Saraste and the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra (recently re-issued as part of a bargain-priced 5CD box with Virgin recordings). It's two minutes faster than Haitink and to me it sounds curiously anemic. The indifferent digital sound doesn't help. Jeux has to be perfectly moulded and played. If not, it quickly bores and that is what happened to me when I listened to this recording.

zondag 23 oktober 2011

Roussel: Bacchus et Ariane, Suite n° 2

|

The Chandos recording made by Neeme Järvi at the beginning of his tenure with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra (early 1990s) sounded bloated and uninvolving. The sparkle that characterised the orchestra's recordings of French repertoire under Paul Paray in the 1950s seemed to have all but gone. Then Stéphane Deneve with the Scottish National Orchestra on Naxos. His series of recordings of Roussel's orchestral works has been critically acclaimed. This CD features the Third Symphony and the two Bacchus suites. Compared to the Järvi, the performance sounds more thought-through and more sophisticated. A nice bonus is that the different sections of the ballet are separately cued so that it is easy to relisten specific episodes. Despite the obvious qualities of the recording I had the persistent feeling that the orchestra was not with its heart in the music. Deneve skillfully guides us through a colourful storybook, spotlighting many of the orchestral felicities, but ultimately fails to really engage us. In the frenzied finale the orchestra seems to go on autopilot. The recording sounds rather cavernous, with the brass ostensibly sitting miles behind the string section. So, I have mixed feelings about this one.

Markevitch and his Lamoureux Orchestra, taped by DGG engineers in 1960, eat these two CDs for breakfast however. It's one of these cheap Resonance pressings but it sounds truly awesome. The recording is admittedly a little dry and airless (I can't detect almost no ambient atmosphere) but that is compensated by the terrific liveliness of the playing. It's as if one is sitting on the concertmaster's lap, so close and realistic is the sound of all the orchestra groups: the barking horns, the swirling winds, the double basses sharp as daggers, the clattering timpani. Listening to this recording one easily forgets the ballet story. It's just a blazing piece of absolute music with the angular and vibrant energy of a Matisse painting. Markevitch keeps an iron hand on the proceedings, nicely moulding the ebb and flow and propelling the Lamoureux to a Dyonisiac finale. Great stuff, no doubt about it.

Debussy: Le Martyre de Saint-Sébastien - Symphonic Fragments

Whilst Pierre Monteux is to be considered an authority when it comes to the music of Debussy - he led the viola section in the orchestra that premiered Pelléas et Mélisande in 1902 - his late recording of the Martyre fragments with the London SO (1963, barely a year before his death) does not unseat Michael Tilson Thomas' grandiose performance with the same orchestra almost 30 years later. Monteux's is certainly a fine reading and it still sounds fresh on LP, but I personally wonder what the point is of listening only to the symphonic fragments when the 'complete' work is of such dazzling beauty. Curiously, the Fragments miss out on the whole of Act 3 which is the whole work's dramatic and musical climax. I did not revisit the MTT recording apart from re-sampling the First Mansion, The Court of Lilies, which comes off splendidly. You can hear how the orchestra, chorus and singers have been rehearsed to perfection. The recording is finely chiseled, spacious and weighty. I've been trying to find more background information on this work, but remarkably it's hardly mentioned in the Cambridge Companion. I've also discovered that the Brussels Philharmonic is going to perform the complete version in Brussels next February 5th. I've marked the date in red in my diary.

zaterdag 22 oktober 2011

Debussy: Le Martyre de Saint Sébastien - Symphonic Fragments

I just listened for the very first time to the symphonic fragments of Debussy's Martyre de Saint Sébastien (in the version by the Los Angeles PO led by Salonen). Didn't know the work at all! What a daringly sophisticated piece of music this is! The haunting orchestration and the amazingly exotic harmonic language capture the atmosphere of a mystery play to perfection. The spectre of Parsifal is everywhere (sometimes very emphatically so) but Debussy goed beyond it, mapping out what seems to me to be virgin territory. Despite the extravagance of the setting and Debussy's musical language there is a spareness and stillness at the heart of this music which is spellbinding. I am at this very moment following up with a more complete selection of both orchestral and sung fragments recorded by the London SO conducted by Tilson-Thomas. And this is even more astonishing. What a freakishly beautiful score ... It's giving me goosepimples all over. It reminds me of the most audacious experiments of Scriabin or the otherworldly soundscapes of Messiaen, a few decades hence. What an amazing discovery ...

vrijdag 21 oktober 2011

Dove: Siren Song

Siren song: this immediately opens up some Debussyean perspectives ...

Jonathan Dove is a contemporary British composer (born in 1959) of predominantly operatic works. Allegedly he has written more than 50 (!) of them, in a variety of formats, from the full-scale stage drama to television, chamber and community operas.

Dove appeared in one of my numerous search campaigns in the databases of Presto Classical or Amazon. Listening to the snippets online I liked what I heard and so I decided to acquaint myself with this composer's work via a shorter, single CD work. It has, by the way, been ages since I listened to opera.

Siren Song (an early work, written in 1994, when Dove was just 35) is a chamber opera developed around the reportedly true story of a sailor who became the victim of an elaborate hoax. Reacting to an add in a newspaper he struck up a correspondence with a British belle from Southampton. The girl, however, did not exist but happened to be a front for an impostor posing as her brother in order to obtain favours and money. This was in 1988, so before the advent of mobile telephony and internet. It's an intriguing story, full of deep resonances, that has been turned into a breezy libretto by the playwright Nick Dear. The work itself has a compact scale, requiring a cast of five singers (the sailor, the girl, the brother and two officials in cameo roles), and a band of only 10 players (flute/piccolo, oboe, clarinet, horn, piano/celesta, harp, percussion, violin, cello and double-bass). It plays in one continuous act, divided into seventeen quasi-cinematographic scenes, lasting about 75 minutes in total.

Clearly Dove has a very lively dramatic instinct and he makes the music subservient to the unfolding narrative. This must be one of the only operas where I found myself truly following the story (easy enough as the singers' diction is so clear) rather than just considering it as a piece of absolute music with voices tacked on. I would describe the style of the music as minimalist. A mix of Adams, Reich and Glass that, surprisingly, doesn't sound trite. There are no big tunes, nothing that musically really jumps out. Instead we have a light, transparent, constantly shifting musical tapestry that is remarkably successful in supporting the action and creating an atmosphere that is shot through with dread and yearning. The vocal writing is very attractive, humane and lyrical, and an ideal foil for the young voices that are featured in this production: Brad Cooper's marvelously youthful tenor, Mattijs van de Woerd's credibly charlatanesque baritone and Amaryllis Dieltiens who, despite a background that is heavily tilted towards the Baroque repertoire, puts down a suitably frivolous siren (Dieltiens is a Belgian soprano who started her musical education at the Leuven Lemmens Institute, here around the corner).

The recording has been made from live performances at the 2007 Grachtenfestival in Amsterdam. It is in all respects excellent. Voices and instruments are well placed and close enough to the microphones to make impact. There is minimal audience intrusion and stage noise. The instrumental ensemble, led by Henk Guittart (primarius of the Schoenberg Quartet until the ensemble's demise in 2009, amongst other achievements), works wonders. So altogether an excellent production that I will be happy to revisit. Meanwhile I have also ordered the Chandos recording of Dove's most notable success, a full-fledged airport comedy called Flight that has been commissioned by Glyndebourne Festival.

I want to briefly come back to those intriguing parallels between this work and Debussy's universe. A distinctive feature of the minimalist style is, of course, the recurring use of ostinatos (or ostinato networks). And this happens to be an important feature of Debussy's music as well. This may, in both instances, go back to the exotic influence of the Javanese gamelan (which Debussy famously heard at the Paris World Exhibition in 1889). Sirènes, the final part of his Nocturnes, is almost wholly built up as a composite ostinato, in which several ostinato-based strands unfold simultaneously. Only in the exact centre of the piece and in very few other isolated places they are absent (I have this from Richard Parks' essay 'Music's inner dance: form, pacing and complexity in Debussy's music' in the Cambridge Companion). Specifically in the context of Debussy's work Derrick Puffett has called this an 'ostinato machine': "a composite ostinato in which each of the separate strands pursues its own rhythmic/harmonic course, together creating a dense polyphonic structure. The 'machine' metaphor is apt as such structures tend to assume a kind of autonomy, unfolding alongside, or even in opposition to, whatever mode of organisation prevails for the piece as a whole." Also Dove's approach of spinning a differentiated, constantly changing musical fabric, without genuine climaxes or epiphanies, is very Debussy-like. (Late in his life, when working with a writer on a text for a cantata on Jeanne d'Arc, Debussy confessed that he 'was suspicious with respect to the exceptional').

Apart from this stylistic correspondence, there is also thematic overlap, it seems to me, with the world of Debussy. First of all, in Dove's opera as in Debussy's work, there is the dominant image (or context) of the sea. The more I listen to Debussy, the more it seems that all of his work is pervaded by a deep fascination for this most powerful manifestation of the undifferentiated, the Real. The sailor's yearning for human companionship and the trivial seductions of domestic life, and hence his willingness to be conned, can only be understood against the background of his life at the very edge of nothingness. I think this was an edge that interested Debussy to a very high degree.

Jonathan Dove is a contemporary British composer (born in 1959) of predominantly operatic works. Allegedly he has written more than 50 (!) of them, in a variety of formats, from the full-scale stage drama to television, chamber and community operas.

Dove appeared in one of my numerous search campaigns in the databases of Presto Classical or Amazon. Listening to the snippets online I liked what I heard and so I decided to acquaint myself with this composer's work via a shorter, single CD work. It has, by the way, been ages since I listened to opera.

Siren Song (an early work, written in 1994, when Dove was just 35) is a chamber opera developed around the reportedly true story of a sailor who became the victim of an elaborate hoax. Reacting to an add in a newspaper he struck up a correspondence with a British belle from Southampton. The girl, however, did not exist but happened to be a front for an impostor posing as her brother in order to obtain favours and money. This was in 1988, so before the advent of mobile telephony and internet. It's an intriguing story, full of deep resonances, that has been turned into a breezy libretto by the playwright Nick Dear. The work itself has a compact scale, requiring a cast of five singers (the sailor, the girl, the brother and two officials in cameo roles), and a band of only 10 players (flute/piccolo, oboe, clarinet, horn, piano/celesta, harp, percussion, violin, cello and double-bass). It plays in one continuous act, divided into seventeen quasi-cinematographic scenes, lasting about 75 minutes in total.

Clearly Dove has a very lively dramatic instinct and he makes the music subservient to the unfolding narrative. This must be one of the only operas where I found myself truly following the story (easy enough as the singers' diction is so clear) rather than just considering it as a piece of absolute music with voices tacked on. I would describe the style of the music as minimalist. A mix of Adams, Reich and Glass that, surprisingly, doesn't sound trite. There are no big tunes, nothing that musically really jumps out. Instead we have a light, transparent, constantly shifting musical tapestry that is remarkably successful in supporting the action and creating an atmosphere that is shot through with dread and yearning. The vocal writing is very attractive, humane and lyrical, and an ideal foil for the young voices that are featured in this production: Brad Cooper's marvelously youthful tenor, Mattijs van de Woerd's credibly charlatanesque baritone and Amaryllis Dieltiens who, despite a background that is heavily tilted towards the Baroque repertoire, puts down a suitably frivolous siren (Dieltiens is a Belgian soprano who started her musical education at the Leuven Lemmens Institute, here around the corner).

The recording has been made from live performances at the 2007 Grachtenfestival in Amsterdam. It is in all respects excellent. Voices and instruments are well placed and close enough to the microphones to make impact. There is minimal audience intrusion and stage noise. The instrumental ensemble, led by Henk Guittart (primarius of the Schoenberg Quartet until the ensemble's demise in 2009, amongst other achievements), works wonders. So altogether an excellent production that I will be happy to revisit. Meanwhile I have also ordered the Chandos recording of Dove's most notable success, a full-fledged airport comedy called Flight that has been commissioned by Glyndebourne Festival.

I want to briefly come back to those intriguing parallels between this work and Debussy's universe. A distinctive feature of the minimalist style is, of course, the recurring use of ostinatos (or ostinato networks). And this happens to be an important feature of Debussy's music as well. This may, in both instances, go back to the exotic influence of the Javanese gamelan (which Debussy famously heard at the Paris World Exhibition in 1889). Sirènes, the final part of his Nocturnes, is almost wholly built up as a composite ostinato, in which several ostinato-based strands unfold simultaneously. Only in the exact centre of the piece and in very few other isolated places they are absent (I have this from Richard Parks' essay 'Music's inner dance: form, pacing and complexity in Debussy's music' in the Cambridge Companion). Specifically in the context of Debussy's work Derrick Puffett has called this an 'ostinato machine': "a composite ostinato in which each of the separate strands pursues its own rhythmic/harmonic course, together creating a dense polyphonic structure. The 'machine' metaphor is apt as such structures tend to assume a kind of autonomy, unfolding alongside, or even in opposition to, whatever mode of organisation prevails for the piece as a whole." Also Dove's approach of spinning a differentiated, constantly changing musical fabric, without genuine climaxes or epiphanies, is very Debussy-like. (Late in his life, when working with a writer on a text for a cantata on Jeanne d'Arc, Debussy confessed that he 'was suspicious with respect to the exceptional').

Apart from this stylistic correspondence, there is also thematic overlap, it seems to me, with the world of Debussy. First of all, in Dove's opera as in Debussy's work, there is the dominant image (or context) of the sea. The more I listen to Debussy, the more it seems that all of his work is pervaded by a deep fascination for this most powerful manifestation of the undifferentiated, the Real. The sailor's yearning for human companionship and the trivial seductions of domestic life, and hence his willingness to be conned, can only be understood against the background of his life at the very edge of nothingness. I think this was an edge that interested Debussy to a very high degree.

dinsdag 18 oktober 2011

Chausson: Poème de l'Amour et de la Mer

Marvelous, this lavish, Wagnerian song-symphony written by Ernest Chausson in the late 1880s. I've always held this recording in high esteem. Waltraud Meier is a commanding voice that soars effortlessly over the orchestral waves that are summoned by a glorious Philadelphia Orchestra. The recording dates from the late 1980s and that must have been the time when I attended a live concert with this orchestra in the Brussels Bozar. Whilst the Philadelphians likely were on the way down from the stratospheric heights they once occupied under the long tenures of Stokowski and Ormandy, I came away mightily impressed. In this recording too the richness of the orchestral sound is still intoxicating. I haven't heard any competing recordings (remarkably, there aren't very many) and it is well possible that the music sounds a little too Teutonic for its own good. Nevertheless I have always enjoyed this reading, with its wonderful fin-de-siècle shadings, its shimmering palette, the long, flowery lines and the pervasive sense of forlornness.

zondag 16 oktober 2011

Milhaud: Le Boeuf sur le Toit

Earlier this week I was listening to a recording of Debussy's Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faun. It was vinyl pressing of a 1950s performance featuring the Detroit Symphony Orchestra led by Paul Paray. The LP side was completed by a recording of Darius Milhaud's Le Boeuf sur le Toit, op. 58 (1919), with the London SO conducted by Antal Dorati. And so we carried on with the Frenchman's exotic, rumbustious pastiche that emerged from a 1917 visit to Brazil. Originally conceived as a fantasia to accompany a Chaplinesque movie, it was soon picked up by Jean Cocteau and turned into a ballet. The music is conceived as a (cinematic) sequence of popular Brazilian tunes interspersed with a rondo-like theme. Milhaud never disclosed the origin of these tunes, referring to them nonchalantly as "a few popular melodies, tangos, maxixes, sambas, even a Portuguese fado" but the assiduous detective work performed by Daniella Thompson and others has revealed that the 28 tunes go back to at least 14 Brazilian composers, some of which were very popular at the time when Milhaud visited the country. Here is an analysis of the piece with reference to all the tunes featured. It is now assumed that only the motto theme was truly Milhaud's. The question to what extent this is a case of ice cold plagiarism continues to be vigorously debated. However, the imbroglio shouldn't spoil our pleasure of listening to this delightful piece.

The two versions I listened to - the aforementioned LP with LSO/Dorati and a CD recording with the Ulster Orchestra, led by Yan Pascal Tortelier - made for two very different experiences. Tortelier's reading is brisk and uniformily loud, turning the tropical fantasia in some sort of orchestral showpiece. Compared to the LP the CD sounds predictably more glossy and cold too. Dorati's take on the Boeuf is slower, taking 3 minutes longer (19' as opposed to Tortelier's 16') and is imbued with a sort of nobility that is wholly absent in the more brash and virtuosic rendering by Tortelier and his Irish orchestra. With Dorati we move more casually through a diversified musical landscape. There is time to breath, to admire the sights and colours that cinematographically bloom and fade before our mind's eye. Dorati's reading draws our attention to the fact that this accessible music, that seems to saunter along quite nonchalantly, must be hard to conduct well.

Whilst the LP still is in need of a KM treatment, it already sounds more three-dimensional and engaging than the CD.

It's remarkable how very rarely this quite accessible and exuberant music is recorded nowadays. Tortelier's is as far as I am aware the only contemporary reading and even that goes back to 1991. Ridiculous how today's young maestros continue to churn out alpine symphonies, heldenlebens, Mahler 9ths and Shostakovich 10ths, whilst disregarding a wealth of clever and engaging repertoire.

The two versions I listened to - the aforementioned LP with LSO/Dorati and a CD recording with the Ulster Orchestra, led by Yan Pascal Tortelier - made for two very different experiences. Tortelier's reading is brisk and uniformily loud, turning the tropical fantasia in some sort of orchestral showpiece. Compared to the LP the CD sounds predictably more glossy and cold too. Dorati's take on the Boeuf is slower, taking 3 minutes longer (19' as opposed to Tortelier's 16') and is imbued with a sort of nobility that is wholly absent in the more brash and virtuosic rendering by Tortelier and his Irish orchestra. With Dorati we move more casually through a diversified musical landscape. There is time to breath, to admire the sights and colours that cinematographically bloom and fade before our mind's eye. Dorati's reading draws our attention to the fact that this accessible music, that seems to saunter along quite nonchalantly, must be hard to conduct well.

Whilst the LP still is in need of a KM treatment, it already sounds more three-dimensional and engaging than the CD.

It's remarkable how very rarely this quite accessible and exuberant music is recorded nowadays. Tortelier's is as far as I am aware the only contemporary reading and even that goes back to 1991. Ridiculous how today's young maestros continue to churn out alpine symphonies, heldenlebens, Mahler 9ths and Shostakovich 10ths, whilst disregarding a wealth of clever and engaging repertoire.

vrijdag 14 oktober 2011

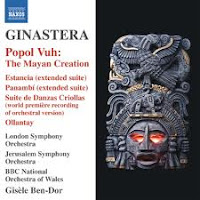

Ginastera: Popol Vuh and other orchestral works

A break from Debussy's delicate watercolours (or pen drawings) with Alberto Ginastera's cartoonish works for orchestra. I hasten to add that I don't want to suggest disdain for this superbly colourful and actually quite sophisticated music. I got to know Ginastera's Estancia, likely his best known work, ages ago on an LP with recordings conducted by Enrico Batiz. At that time it didn't make a lasting impression. But this CD surprised me with an unexpected level of compositional skill and refinement. Another aspect that turned my ears red is the jaw-dropping energy that the female conductor Gisèle Ben-Dor of Israeli extraction (unbeknownst to me) brings to the performance of these pieces. Particularly in the two ballet suites - Panambia op. 1 and Estancia op. 8 - the London SO seem to be at the very edge of their seats!

Stylistically, these pieces oscillate between athletic primitivism and a poignant, rustic lyricism à la Copland (with whom Ginastera studied). They are symphonic spectaculars in the true sense of the word, featuring an abundance of explosive rhythms and memorable tunes. What also strikes is Ginastera's fantastic mastery of the orchestra, even in his op. 1 which he wrote at the tender age of 20.

In addition to the ballet suites the CD features three orchestral works that come more or less from the same mould. The Suite of Native Dances op. 15 is very short and probably the least memorable of the package. Ollantay (A Symphonic Tryptich), op. 17 is much more substantial. It's, as so often with Ginasteria, inspired by Incan lore. Here the colours are more muted and the symphonic argument more differentiated than in the suites. The most notable piece on this CD is the unfinished opus Popol Vuh: The Mayan Creation, op. 44. Allegedly this was a commission by Eugene Ormandy which Ginastera was very slow to take up and eventually he continued to work on it for almost 20 years. It was still unfinished by the time of his death in 1983. But 8 of the 9 planned sections were performable and the premiere took place in 1989 by Leonard Slatkin and the St Louis Symphony. Popol Vuh is a 25 minute orchestral fantasy that is a cross between, say, Varèse and Ravel. The Mayan creation is depicted as a sequence of expressionistic orchestral tableaux that ascend from the depths of The Everlasting Night to the Dawn of Mankind. I can't detect a deep symphonic logic in it, but there is no denying that this piece provides evidence of an unflagging creativity and an unbroken musical imagination.

Popol Vuh and Ollantay are very capably performed by the BBC Welsh Orchestra with Ben-Dor at the helm. Although the CD collates recordings with different orchestras and venues, the sonic picture is remarkably consistent. The sound is rather resonant, with fairly good bass and mid-range but a mushy top end. As a result in the most frenzied tuttis the orchestra tends to shrink into a blur. But I'm not complaining as this CD has given me a good deal of listening pleasure.

Stylistically, these pieces oscillate between athletic primitivism and a poignant, rustic lyricism à la Copland (with whom Ginastera studied). They are symphonic spectaculars in the true sense of the word, featuring an abundance of explosive rhythms and memorable tunes. What also strikes is Ginastera's fantastic mastery of the orchestra, even in his op. 1 which he wrote at the tender age of 20.

In addition to the ballet suites the CD features three orchestral works that come more or less from the same mould. The Suite of Native Dances op. 15 is very short and probably the least memorable of the package. Ollantay (A Symphonic Tryptich), op. 17 is much more substantial. It's, as so often with Ginasteria, inspired by Incan lore. Here the colours are more muted and the symphonic argument more differentiated than in the suites. The most notable piece on this CD is the unfinished opus Popol Vuh: The Mayan Creation, op. 44. Allegedly this was a commission by Eugene Ormandy which Ginastera was very slow to take up and eventually he continued to work on it for almost 20 years. It was still unfinished by the time of his death in 1983. But 8 of the 9 planned sections were performable and the premiere took place in 1989 by Leonard Slatkin and the St Louis Symphony. Popol Vuh is a 25 minute orchestral fantasy that is a cross between, say, Varèse and Ravel. The Mayan creation is depicted as a sequence of expressionistic orchestral tableaux that ascend from the depths of The Everlasting Night to the Dawn of Mankind. I can't detect a deep symphonic logic in it, but there is no denying that this piece provides evidence of an unflagging creativity and an unbroken musical imagination.

Popol Vuh and Ollantay are very capably performed by the BBC Welsh Orchestra with Ben-Dor at the helm. Although the CD collates recordings with different orchestras and venues, the sonic picture is remarkably consistent. The sound is rather resonant, with fairly good bass and mid-range but a mushy top end. As a result in the most frenzied tuttis the orchestra tends to shrink into a blur. But I'm not complaining as this CD has given me a good deal of listening pleasure.

donderdag 13 oktober 2011

Debussy: Violin Sonata - Cello Sonata - Sonata for Flute, Viola and Harp - Syrinx

We're continuing to impregnate ourselves with Debussy's wonderful late sonatas, this time in a very compelling reading by members of the London-based Nash Ensemble. These are Virgin recordings that have been originally issued in the early 1990s. Now they are re-issued as part of a 5CD box sold at a fire sale price (14 euro to be precise).

The Violin Sonata remains my favourite. I am astonished that compared to the other sonatas it receives short shrift in most of what I have read about Debussy. Marcel Dietschy in his "A Portrait of Claude Debussy" finds it 'unbalanced'. Victor Lederer in his "Quiet Revolutionary" also thinks it is 'less imaginative' than the companion pieces. Balderdash! It's a forceful, heartwrenching piece that leaves me dumbfounded every time I hear it. The reading here by Marcia Crayford on violin and Ian Brown on piano is particularly successful. The two musicians take their time, stretching the first movement just over five minutes, as a result of which it almost sounds didactic. But that doesn't equate with 'stodgy' or 'characterless'. Quite the contrary, there's a levelheadedness and honesty to the playing that is quite affecting. The Allegro's slower tempo reinforces the music's stoic mournfulness. I just would have wished a tad more angst in that final cry of anguish that brings the introductory movement to a devastating end. The faster movements are delivered with similar composure, illuminating the wistful rather than the fantastic side of this layered score. I was really moved by it. Being so impressed by this level of musicianship I looked up the background and whereabouts of Marcia Crayford. Having studied with Yehudi Menuhin, she led the Nash Ensemble for 25 years, until 1995, after which she went on to become the London SO's concert master. Recently she has said the bustle of the capital goodbye and has taken up the leadership of a new regional chamber orchestra in the midst of rural Wales.

The Cello Sonata with Christopher van Kampen (who sadly passed away at a relatively young age in 1997; he had been married and divorced to Marcia Crayford) is equally rewarding and shares some of the traits of the companion recording of the Violin Sonata. It's sobriety is a relief after the larger than life histrionics of the Maisky-Argerich partnership.

I was particularly curious about the trio sonata as the reading by the Melos Ensemble had left me so dissatisfied. Happily enough, this version (with Philippa Davies on flute, Roger Chase on viola and Marisa Robles on harp) seems to make a much more convincing case for this piece. I can start to sense an overall form and direction now. But I'm not yet at the point yet where I share the unreserved admiration of many commentators (de Falla thought it was 'music for Paradise'; I read someone else who curiously enough compared the sonata to 'Jeux'). It will take me a few more auditions to get a handle on this piece.

Finally, kudos to Philippa Davies for Syrinx, a wonderful flute arabesque composed in 1913 that reminisces about earlier milestones in Debussy's artistic path, notably the Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faun.

The Violin Sonata remains my favourite. I am astonished that compared to the other sonatas it receives short shrift in most of what I have read about Debussy. Marcel Dietschy in his "A Portrait of Claude Debussy" finds it 'unbalanced'. Victor Lederer in his "Quiet Revolutionary" also thinks it is 'less imaginative' than the companion pieces. Balderdash! It's a forceful, heartwrenching piece that leaves me dumbfounded every time I hear it. The reading here by Marcia Crayford on violin and Ian Brown on piano is particularly successful. The two musicians take their time, stretching the first movement just over five minutes, as a result of which it almost sounds didactic. But that doesn't equate with 'stodgy' or 'characterless'. Quite the contrary, there's a levelheadedness and honesty to the playing that is quite affecting. The Allegro's slower tempo reinforces the music's stoic mournfulness. I just would have wished a tad more angst in that final cry of anguish that brings the introductory movement to a devastating end. The faster movements are delivered with similar composure, illuminating the wistful rather than the fantastic side of this layered score. I was really moved by it. Being so impressed by this level of musicianship I looked up the background and whereabouts of Marcia Crayford. Having studied with Yehudi Menuhin, she led the Nash Ensemble for 25 years, until 1995, after which she went on to become the London SO's concert master. Recently she has said the bustle of the capital goodbye and has taken up the leadership of a new regional chamber orchestra in the midst of rural Wales.

The Cello Sonata with Christopher van Kampen (who sadly passed away at a relatively young age in 1997; he had been married and divorced to Marcia Crayford) is equally rewarding and shares some of the traits of the companion recording of the Violin Sonata. It's sobriety is a relief after the larger than life histrionics of the Maisky-Argerich partnership.

I was particularly curious about the trio sonata as the reading by the Melos Ensemble had left me so dissatisfied. Happily enough, this version (with Philippa Davies on flute, Roger Chase on viola and Marisa Robles on harp) seems to make a much more convincing case for this piece. I can start to sense an overall form and direction now. But I'm not yet at the point yet where I share the unreserved admiration of many commentators (de Falla thought it was 'music for Paradise'; I read someone else who curiously enough compared the sonata to 'Jeux'). It will take me a few more auditions to get a handle on this piece.

Finally, kudos to Philippa Davies for Syrinx, a wonderful flute arabesque composed in 1913 that reminisces about earlier milestones in Debussy's artistic path, notably the Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faun.

zondag 9 oktober 2011

Comment: A Year of Blogging

I've been maintaining this listening diary now for just over a year. It has certainly been an experience that has revolutionised my listening habits. I almost can't imagine anymore how I used to listen before I started to document my listening trajectory.

One of the very obvious benefits has been a considerable expansion of repertoire. I have discovered so many new things over the past year that I feel rejuvenated as a music lover. And I can see vast unexploited tracks of repertoire stretching out in front of me. Also I feel I have gained a much better, more differentiated view of 20th century music history, particularly of this important 1920-1960 time bracket during which so much was going on.

Another good thing has been the slowing down and the concomitant increase in quality of listening. Background listening has almost completely disappeared (I can remember the time when, blasphemously, I had music on in my office whilst working!). Listening, reflecting, looking things up and writing things down has become almost a meditative discipline. In addition it's just a matter of respect for the meaning and quality of the music making. I want to hang onto that.

A potential risk, I found, is an inclination to compartmentalise the musical experience too much. If I'm not careful I have the tendency to overplan and overrationalise. That is counterproductive. So I need to find a way to mix rigour and spontaneity (almost in a Debussyan way). I think I can do that. The whole Bartok chapter emerged almost accidentally from my unsuspecting approach to Kodaly. The Debussy trace I'm following now emerged simply from a De Falla piece that spilled over into a Debussy sonata. I think that these spontaneously emerging attractors are a good thing. Each of these create new lines which I can follow as long as I like. So now I have Bartok, string quartets, Spanish/Iberian music and Debussy as main listening tracks. New ones will be added and after a while some will whither.

What the listening diary has not done is to bring me closer to understanding the enigma of music. I agree it is very naive to think that we can 'solve' this riddle. But I am inclined to believe we can at least make some progress towards doing so. But the diary has rather produced the contrary: at no time music has appeared more bafflingly mysterious to me than it does today.

One of the very obvious benefits has been a considerable expansion of repertoire. I have discovered so many new things over the past year that I feel rejuvenated as a music lover. And I can see vast unexploited tracks of repertoire stretching out in front of me. Also I feel I have gained a much better, more differentiated view of 20th century music history, particularly of this important 1920-1960 time bracket during which so much was going on.

Another good thing has been the slowing down and the concomitant increase in quality of listening. Background listening has almost completely disappeared (I can remember the time when, blasphemously, I had music on in my office whilst working!). Listening, reflecting, looking things up and writing things down has become almost a meditative discipline. In addition it's just a matter of respect for the meaning and quality of the music making. I want to hang onto that.

A potential risk, I found, is an inclination to compartmentalise the musical experience too much. If I'm not careful I have the tendency to overplan and overrationalise. That is counterproductive. So I need to find a way to mix rigour and spontaneity (almost in a Debussyan way). I think I can do that. The whole Bartok chapter emerged almost accidentally from my unsuspecting approach to Kodaly. The Debussy trace I'm following now emerged simply from a De Falla piece that spilled over into a Debussy sonata. I think that these spontaneously emerging attractors are a good thing. Each of these create new lines which I can follow as long as I like. So now I have Bartok, string quartets, Spanish/Iberian music and Debussy as main listening tracks. New ones will be added and after a while some will whither.

What the listening diary has not done is to bring me closer to understanding the enigma of music. I agree it is very naive to think that we can 'solve' this riddle. But I am inclined to believe we can at least make some progress towards doing so. But the diary has rather produced the contrary: at no time music has appeared more bafflingly mysterious to me than it does today.

Debussy: Nocturnes

Debussy's Nocturnes is this composer's opus I likely know best. Despite having listened to it quite often over the years it has always remained a bit of a closed book to me. It's beautiful music, of course, and quite easy and pleasant to listen too. But I have never found it to really catch fire. Again, as with Jeux, it's more a matter of intellectual admiration rather than genuine enthusiasm. I think it also very difficult to pull off well as an orchestra. For the most part it is not spectacular music and top soloists (particularly in the winds) are needed to breathe life in the sparse textures. I'd love to hear a version by the Budapest Festival Orchestra who have the delicacy and strength to do something extraordinary with it. But that recording does not exist.

I listened to a couple of versions. First a very dull reading by the Los Angeles Philarmonic led by Salonen. The muffled (20-bit) recording (from Royce Hall, UCLA) did nothing to enliven an experience of stifling boredom.

Then Abbado on a beautiful single LP (in a separate box) with the Boston SO. I gave this LP a cursory listen when it came back from the KM treatment and was very much taken by the beautiful, very spacious recording. But now it struck me as being much too airy, dissolving a lot of the orchestral detail in the surrounding ambience. I compared with the corresponding version on CD which has been significantly reengineered and sounds very dry and boxy.

Another reading by Abbado can be accessed via the Berlin PO's Digital Concert Hall (striking, by the way, how very little music by Debussy has been played during the last seasons). It's a concert from 1998, when Abbado was still the orchestra's chief conductor, in the rather curious surroundings of the VASA museum in Stockholm (with the noble warship looming above the orchestra). How quaint and nerdy the Berliners looked in those days! Not a bad reading but, again, not something that gave me goosepimples.

The best experience, as could be expected, was the lauded performance by Haitink and the Concertgebouw Orchestra. This double CD with all the key orchestral works is justly regarded as a cornerstone of the Debussy discography. The sophistication of the orchestral playing is matched by a super-smooth and silky recording. And even there I remain a rather dispassionate listener.

It may well be that I will never be a genuine Debussyan. It's not an accident that it's precisely his late work that leads me to explore his work in more depth. Because a Debussy 'sonata' is, in a way, an oxymoron. His greatness lies precisely in his resistance to these conflict-driven formal templates from the past. Debussy is not a symphonist and most consciously did not want to be constrained by these forms. Instead he did not go down the path of expressionistic fragmentation but relied on a compositional strategy of 'transformational networks' "which treat the musical material as a mixture of motivic and harmonic components in a logically evolving rather than a stratified context" (Arnold Whittal quoting David Lewin in his contribution to the Cambridge Companion to Debussy). Instead of 'logically evolving' it would perhaps be better to talk about 'organically evolving' as formally and harmonically the music charts a process in which continuity and change interact. Eliott Carter spoke of "coherent, ever changing continuities". Another revealing quote from the same article, this time Whittal quoting Robert P. Morgan: "the music never degenerates into a series of pleasant yet unrelated effects, a succession of isolated musical moments; everything is held together by a tight network of melodic, rhythmic, and harmonic associations ... (nevertheless) the type of musical form he developed is more loosely connected and more 'permeable' ... than that of traditional tonal music. His conception of form as essentially 'open' in character was to have an important influence on much later twentieth-century music". In a way it's reassuring that up to this day also skilled music analysts can't find a satisfactory algorithm to decode Debussy's music. Maybe we need to convince complexity theorists and agent-based modellers to have a look, as these are scientists used to let complex, organic structures flower from modest cells.

I listened to a couple of versions. First a very dull reading by the Los Angeles Philarmonic led by Salonen. The muffled (20-bit) recording (from Royce Hall, UCLA) did nothing to enliven an experience of stifling boredom.

Then Abbado on a beautiful single LP (in a separate box) with the Boston SO. I gave this LP a cursory listen when it came back from the KM treatment and was very much taken by the beautiful, very spacious recording. But now it struck me as being much too airy, dissolving a lot of the orchestral detail in the surrounding ambience. I compared with the corresponding version on CD which has been significantly reengineered and sounds very dry and boxy.

Another reading by Abbado can be accessed via the Berlin PO's Digital Concert Hall (striking, by the way, how very little music by Debussy has been played during the last seasons). It's a concert from 1998, when Abbado was still the orchestra's chief conductor, in the rather curious surroundings of the VASA museum in Stockholm (with the noble warship looming above the orchestra). How quaint and nerdy the Berliners looked in those days! Not a bad reading but, again, not something that gave me goosepimples.

The best experience, as could be expected, was the lauded performance by Haitink and the Concertgebouw Orchestra. This double CD with all the key orchestral works is justly regarded as a cornerstone of the Debussy discography. The sophistication of the orchestral playing is matched by a super-smooth and silky recording. And even there I remain a rather dispassionate listener.

It may well be that I will never be a genuine Debussyan. It's not an accident that it's precisely his late work that leads me to explore his work in more depth. Because a Debussy 'sonata' is, in a way, an oxymoron. His greatness lies precisely in his resistance to these conflict-driven formal templates from the past. Debussy is not a symphonist and most consciously did not want to be constrained by these forms. Instead he did not go down the path of expressionistic fragmentation but relied on a compositional strategy of 'transformational networks' "which treat the musical material as a mixture of motivic and harmonic components in a logically evolving rather than a stratified context" (Arnold Whittal quoting David Lewin in his contribution to the Cambridge Companion to Debussy). Instead of 'logically evolving' it would perhaps be better to talk about 'organically evolving' as formally and harmonically the music charts a process in which continuity and change interact. Eliott Carter spoke of "coherent, ever changing continuities". Another revealing quote from the same article, this time Whittal quoting Robert P. Morgan: "the music never degenerates into a series of pleasant yet unrelated effects, a succession of isolated musical moments; everything is held together by a tight network of melodic, rhythmic, and harmonic associations ... (nevertheless) the type of musical form he developed is more loosely connected and more 'permeable' ... than that of traditional tonal music. His conception of form as essentially 'open' in character was to have an important influence on much later twentieth-century music". In a way it's reassuring that up to this day also skilled music analysts can't find a satisfactory algorithm to decode Debussy's music. Maybe we need to convince complexity theorists and agent-based modellers to have a look, as these are scientists used to let complex, organic structures flower from modest cells.

Debussy: Violin Sonata - Cello Sonata - Sonata for Flute, Viola and Harp

Another go at the late Debussy sonatas. I ordered a disc with the Violin Sonata played by Kyung Wha Chung and Radu Lupu, both in their prime in the late seventies. It's a very accomplished recording but does not unsettle the Ferschtman (and live Ibragimova) versions I have been listening too earlier. Certainly good to have.

The book Debussy: The Quiet Revolutionary by Victor Lederer, in the Unlocking the Masters series) contains a CD that includes a recording of the Cello Sonata played by Mischa Maisky and Martha Argerich (a live recording previously released on DGG). It's not a convincing reading: too self-conscious and pompous in a way. I'd rather have the lean, somewhat understated classicism that speaks from the Rossler/Würtz recording on Brilliant.

Finally, the Sonata for Flute, Viola and Harp which is the most elusive part of this valedictory tryptich. It's a strange, very fin de siècle ensemble of rather diffident instruments. And it also sounds that way: sensual, tentative, ostentatiously unvirtuosic. But to my ears it also comes across as short-breathed and confused. I am not sure what to make of it. Debussy himself referred to it as sprung from a very bleak mood but the music shows a remarkable equanimity. Lederer in his book is very laudatory about the work, placing it a notch above the violin sonata. That's quite a mystery to me as it is the violin sonata that comes across as a towering achievement.

The book Debussy: The Quiet Revolutionary by Victor Lederer, in the Unlocking the Masters series) contains a CD that includes a recording of the Cello Sonata played by Mischa Maisky and Martha Argerich (a live recording previously released on DGG). It's not a convincing reading: too self-conscious and pompous in a way. I'd rather have the lean, somewhat understated classicism that speaks from the Rossler/Würtz recording on Brilliant.

Finally, the Sonata for Flute, Viola and Harp which is the most elusive part of this valedictory tryptich. It's a strange, very fin de siècle ensemble of rather diffident instruments. And it also sounds that way: sensual, tentative, ostentatiously unvirtuosic. But to my ears it also comes across as short-breathed and confused. I am not sure what to make of it. Debussy himself referred to it as sprung from a very bleak mood but the music shows a remarkable equanimity. Lederer in his book is very laudatory about the work, placing it a notch above the violin sonata. That's quite a mystery to me as it is the violin sonata that comes across as a towering achievement.

zaterdag 1 oktober 2011

Debussy: Jeux - Ravel: Rhapsodie Espagnole

Some more late Debussy with Jeux, his last and also what is generally regarded his most accomplished and enigmatic orchestral score. Originally written as 'poème dansé' for the Ballets Russes, it was premiered in 1913 by Pierre Monteux and then largely forgotten, supposedly because of its banal scenario (a boy and two girls frolic in a garden at dusk; their game is interrupted by a stray tennis ball). De Sabata recorded it for the first time in 1947 (apparently still available at Testament) and in the 1950s it started to be taken up by a number of francophone conductors (Cluytens, Ansermet, Munch, and again Monteux).

Allegedly Debussy did not like the ballet's plot, but he was ill with cancer and in debt and Dhiagilev paid him 10.000 gold francs to write the score. All of the 700 bars of Jeux were written in just a matter of three weeks in August 1913. Maybe the speed of writing helps to explain the very particular character of this piece. It is as fellow-composer Kevin Volans once wrote about how painter Philip Guston inspired him by his way of working: " ... in an effort to get away from form and into the material, he stood close up to the canvas, working quickly and not stepping back to look until the work was finished." Reflecting on his own quartet The Songlines Volans writes: "I juxtaposed very different kinds of music in the order they occured to me, not thinking ahead, and allowing the material to unfold at its own pace. If there was a 'sense of form' at work, it was covert. However, I didn't use everything that occured to me. I tried to follow Guston's suggestion of 'eliminating both that which is yours already and that which is not yet yours' - in other words, keeping only that which is becoming yours."

I feel this perfectly captures the kaleidoscopic nature of this score in which there are 60 tempo markings and in which myriads of one or two bar motives have been identified. Personally I find it a rather frigid beauty that appeals more to the intellect than to the heart. I listened to three different versions of the work: Tilson Thomas with the London SO, Boulez with the Junge Deutsche Philharmonie (part of their 3CD Jubiläums Edition) and the celebrated Haitink with the Concertgebouw Orchestra. All of them seemed to have an excellent measure of the score, with MTT infusing the music with a characteristically impressionistic sfumato (helped by an atmospheric recording from the Abbey Road Studios), and Boulez, predictably, betting everything on precision and transparency. Haitink is sitting somewhere in between. Despite the qualities of these recordings I have the feeling that there is more to this score.

The CD with the Boulez take on Jeux also includes a 1980 performance by the Junge Deutsche Philharmonie of Ravel's Rhapsodie Espagnole, this time conducted by Kyrill Kondrashin. I've known the Rhapsodie for a very long time (my dad bought a recording in the earliest days of the compact disc medium, Eduardo Mata with the Dallas SO on RCA) considering it as one of these superbly crafted but innocuous symphonic spectaculars. But this performance is of a totally different calibre than anything else I have heard of this piece. It sounds raucously contemporary (I thought it was a later piece than the Debussy Jeux but was surprised to see Ravel composed it in 1907-08 already) and conjures the kind of cataclysmic images that would flower in La Valse only fifteen years and a world war later. The recording, that was made of a live performance, is astonishingly detailed if only a little constricted in the very loudest tutti. Kondrashin and his young orchestra present the work as if every detail has been thought through, yet the music making has an athletic, feline quality that is totally appropriate. It's a spooky, monumental version of the piece that perfectly seems to capture the atmosphere of these heady days early in the previous century.

Allegedly Debussy did not like the ballet's plot, but he was ill with cancer and in debt and Dhiagilev paid him 10.000 gold francs to write the score. All of the 700 bars of Jeux were written in just a matter of three weeks in August 1913. Maybe the speed of writing helps to explain the very particular character of this piece. It is as fellow-composer Kevin Volans once wrote about how painter Philip Guston inspired him by his way of working: " ... in an effort to get away from form and into the material, he stood close up to the canvas, working quickly and not stepping back to look until the work was finished." Reflecting on his own quartet The Songlines Volans writes: "I juxtaposed very different kinds of music in the order they occured to me, not thinking ahead, and allowing the material to unfold at its own pace. If there was a 'sense of form' at work, it was covert. However, I didn't use everything that occured to me. I tried to follow Guston's suggestion of 'eliminating both that which is yours already and that which is not yet yours' - in other words, keeping only that which is becoming yours."

I feel this perfectly captures the kaleidoscopic nature of this score in which there are 60 tempo markings and in which myriads of one or two bar motives have been identified. Personally I find it a rather frigid beauty that appeals more to the intellect than to the heart. I listened to three different versions of the work: Tilson Thomas with the London SO, Boulez with the Junge Deutsche Philharmonie (part of their 3CD Jubiläums Edition) and the celebrated Haitink with the Concertgebouw Orchestra. All of them seemed to have an excellent measure of the score, with MTT infusing the music with a characteristically impressionistic sfumato (helped by an atmospheric recording from the Abbey Road Studios), and Boulez, predictably, betting everything on precision and transparency. Haitink is sitting somewhere in between. Despite the qualities of these recordings I have the feeling that there is more to this score.

The CD with the Boulez take on Jeux also includes a 1980 performance by the Junge Deutsche Philharmonie of Ravel's Rhapsodie Espagnole, this time conducted by Kyrill Kondrashin. I've known the Rhapsodie for a very long time (my dad bought a recording in the earliest days of the compact disc medium, Eduardo Mata with the Dallas SO on RCA) considering it as one of these superbly crafted but innocuous symphonic spectaculars. But this performance is of a totally different calibre than anything else I have heard of this piece. It sounds raucously contemporary (I thought it was a later piece than the Debussy Jeux but was surprised to see Ravel composed it in 1907-08 already) and conjures the kind of cataclysmic images that would flower in La Valse only fifteen years and a world war later. The recording, that was made of a live performance, is astonishingly detailed if only a little constricted in the very loudest tutti. Kondrashin and his young orchestra present the work as if every detail has been thought through, yet the music making has an athletic, feline quality that is totally appropriate. It's a spooky, monumental version of the piece that perfectly seems to capture the atmosphere of these heady days early in the previous century.

Abonneren op:

Reacties (Atom)